Welcome back to our series on curiosity! In the first article, we covered what happenings in our brains when we become curious. We also noted that just being in a state of curiosity can improve memory, even for things you’re not curious about.

Now let’s explore how we can put students into a state of curiosity.

How To Create Curiosity

It’s worth noting: there’s a difference between “state” and “trait” curiosity.

- Trait Curiosity Some people we know are simply curious people. We’d say they have the trait of curiosity. And who knows how they got it!

- State Curiosity Experiencing a temporary period of curiosity.

Even for folks who we might not consider very curious, we can still put them into a temporary “state” of curiosity and get that dopamine flowing.

So we can’t use “my students just aren’t curious” as an excuse!

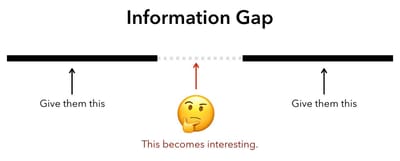

We Have To Know Something

Here’s one key: to become curious, you must already know something about the topic. Curiosity only fires up when we realize that some important information is missing or that it contradicts information we already had. George Loewenstein calls this the Information Gap theory of curiosity.

Simply put, we have to give students enough information for them to become curious about the missing information – or they won’t even realize they’re missing information!

In this curiosity study, one test subject was made curious through Beatles trivia. He already knew enough about the Beatles for this trivia to interest him. If he knew nothing about The Fab Four, that same trivia would have been a total bore.

If we want students to become curious, we must prepare that curiosity with sufficient context.

Watch These Kids React To New Information

Buckle up! You’re about to watch two kids watching the end of The Empire Strikes Back for the first time. You’ll see them react to Darth Vader’s Big Secret™ (40-year-old spoiler alert).

I use this video in workshops to show how powerful it is to reveal new information that doesn’t fit with an existing understanding or, in other words, create some calculate confusion.

Did you watch it? Amazing, right? A physical reaction to information! An emotional roller coaster! All because this new information didn’t match their previous understanding.

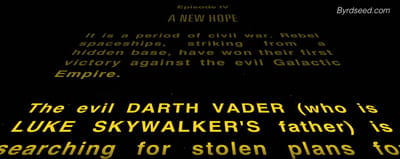

Same Information, Different Reaction

Now imagine if this exact same information were given out at the very beginning of the first Star Wars movie:

It’s the exact same information, but no one’s jaw is going to drop if we present it like this. We haven’t built up enough background knowledge to even understand that this is interesting!

In the video, those kids have watched nearly five hours of Star Wars. They care about the characters and have a mental model for how their relationships work. Darth Vader’s Big Secret™ is shocking given the correct context, but boring without it.

Curiosity Requires Confusion

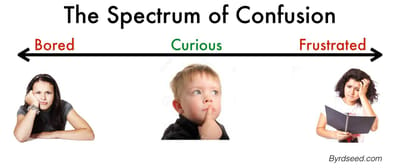

Take note: these kids are confused by this new information. It absolutely disturbed their understanding of Star Wars.

And they LOVE IT!

That’s right, folks, confusion can be delightful! Confusion can create curiosity, which leads to dopamine and a pleasant feeling in our brain (and enhanced memory).

Of course, that confusion must be carefully planned, built up with sufficient background knowledge, and presented in a safe way. Lewenstein would say that the “information gap” isn’t too big. The kids can recover from it.

There’s a spectrum of confusion. Not enough and information is boring. Too much and it’s frustrating. Just right and it provokes curiosity.

Cognitive Disequilibrium

Good ol’ Jean Piaget had a way better name for this feeling than confusion. He called it “cognitive disequilibrium!”

I love this so much. I picture a brain riding a bike and wobbling around. We can’t quite keep our thoughts balanced. It’s even fun to say: cognitive dis•eq•uil•ib•ri•um.

Here’s a clip from my Puzzlement mailers that creates pleasent cognitive disequilibrium. Watch it and consider the dopamine levels in your brain as you become increasingly confused. Note how your disequilibrium builds up, and how much you look forward to seeing “how it works.”

Note: if you only watched the final revelation (the “answer”) it would not have been as interesting. You needed the confusion to build context for the answer. In fact, if we delayed the answer until tomorrow, it would build your curiosity up even more. Anticipation is powerful.

So, strange question, but how often do you purposefully confuse your students?

Summary

To wrap up part two:

- Curiosity requires us to know something about the topic.

- We become curious when information doesn’t fit an existing mental model.

- Confusion is part of curiosity. We enjoy a certain amount of cognitive disequilibrium.

- But! No one wants to be curious forever. It must be resolved.