Our reading program’s comprehension skills have become way too basic for my students.

The material asks:

What do you notice about the character? How can you tell?

This leads to not-so-great student responses like:

Brian is scared. I can tell because he is frightened.

Charlotte is brave. I can tell because she is courageous.

Mr. Sugihara is selfless. I can tell because he is not selfish.

ugh 😑

Let’s differentiate this skill by adding higher-level language:

- explicit details

- implicit details

I’ll also add in a chance to show students some classic art.

Hook and Model

Ask an athletic student to stand up in class.

Class, I think this student is skilled at basketball.

I’d write this detail down on one half of your paper. Then, I’d ask for evidence that backs up my statement. I write their responses on the other side.

| Frank is good at basketball. | “He is wearing basketball shorts” “He’s the tallest person in the class” “His hands are dirty from the basketball court” “His shirt has LeBron James on it” |

I’d explain how we had to use “explicit details” to prove our “implicit detail.” There’s no sign on Frank that says, “I’m athletic.” I’d establish a big idea:

Explicit details reveal implicit details.

Practice With A Portrait

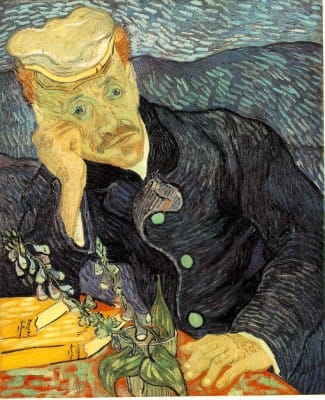

Now you’ll need a visual with implicit and explicit details to demonstrate. I’ve picked Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet. This has the double benefit of exposing my students to a classic (and being in the public domain).

Begin by asking for an implicit detail, what is this man’s mood?

- He’s sad!

- He’s unhappy!

- He’s distraught! (encourage high-level vocabulary)

Now ask for the explicit details that prove this implicit detail. Remind students that an explicit detail is “on the surface” or something that we can point to. Demand exactness and specificity in these details.

- His eyes are sloping down.

- His head is resting on his hand.

- The picture is blue.

- The man is frowning.

Now you’re going to move this information into a paragraph. Explain that the implicit detail becomes a topic sentence.

Dr. Gachet is a distraught man.

Next, the explicit details prove that the topic is true. Use the explicit details your students generated to write the rest of the paragraph.

Dr. Gachet is a distraught man. Van Gogh shows this through Dr. Gachet’s frown. The downward slope of his eyes also demonstrates sadness. Finally, Dr. Gachet is resting his head in his hand in a way that confirms his unhappiness.

Analyze: Compare and Contrast Portraits

As we move to small groups or partners, I’d raise the thinking skill to Analyze (which is always my target). We’re going to compare and contrast explicit details in two portraits.

I had two ideas. You could choose either option:

To me, Dr. Gachet and The Girl with the Pearl Earring are both sort of melancholy yet the styles totally different. We’d be prompting: Agree or Disagree? These paintings have similar moods, yet the details are quite different.

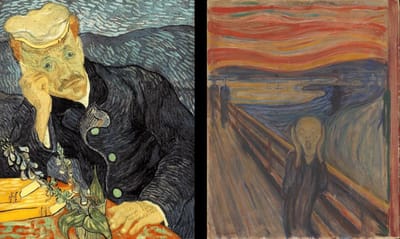

Now, Dr. Gachet and The Scream have similar impressionist styles, yet their moods are not similar at all. I’d ask: Agree or Disagree? These paintings have similar details, yet the moods are quite different.

We’re getting students discussing how two paintings use explicit and/or implicit details differently. This is an interesting topic! Your students might want to stay in from recess to continue this chat :)

Independent Practice: Literature

Now we’re getting to the meat. In 6th grade, this skill goes with Hatchet. But of course it’s one measly chapter devoid of any larger context! What I like to do is supplement our reading selections with classic literature. In this case, I grabbed some of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland from Project Gutenberg.

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, ‘and what is the use of a book,’ thought Alice ‘without pictures or conversation?’

So she was considering in her own mind, whether the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

My students looked for explicit details that implied what Alice is like.

Related Videos For Byrdseed.TV Members